No clear solutions as weather keeps plunging U.S. into darkness

LANSING, Mich. – With disasters striking faster than utility companies and power grid managers can handle, millions are being left in the dark.

When the power unexpectedly goes out in the U.S., seven out of 10 times, it’s because of weather.

More than 32,000 power outages occurred in the U.S. from February 2008 through December 2017, affecting more than 215 million people, according to Eaton, a power management company that tracked blackouts until 2018.

The No. 1 cause of outages were attributed to “weather and/or falling trees,” with 10,667 outages making up nearly 33% of the total. Although not all weather events are natural disasters, most natural disasters are considered weather events.

But the percentage of customers affected by those weather outages was nearly 72%. This means more than 154 million customers lost power in weather events, including Superstorm Sandy in the Northeast, Hurricane Ike in Houston and the Tubbs Fire in Northern California, to name a few.

Since Eaton stopped recording U.S. blackouts 18 months ago, experts say there's no organization publicly tracking power outages on a national level.

Romney Duffey, a nuclear scientist and power restoration researcher in Idaho, has conducted research on safety and risk measures after the nuclear disasters in Fukushima, Japan, and Chernobyl, Ukraine.

Duffey’s recent research on power restoration trends after disasters is the first of its kind to use real-time data. The research, published in 2018, revealed once access and disruption gets bad enough after a disaster, the time it takes to get power back is the same.

“The restoration trends are identical for major wildfires and most severe hurricanes despite their totally disparate origins,” Duffey wrote in his study’s conclusion.

Even though restoring power after a disaster has been an issue since the first light bulb flickered on 140 years ago, federal energy standards have been around for fewer than 15 years.

The Energy Policy Act (EPAct), passed in 2005, was one of the country’s first attempts at regulating energy. Some of the goals of the bill were to foster a competitive power market, strengthen regulations and encourage the development of new energy management equipment for the grid.

But it doesn’t always work.

Life without light

The longest blackout in U.S. history began in 2017 when Hurricane María made landfall in Puerto Rico as a strong Category 4 storm. Recovery efforts were arduous, and some work continues nearly two years later.

In Orocovis, a rural community in central Puerto Rico, Luis Rosado focused on keeping the insulin cold. He and his 11-year-old daughter are diabetic and require daily insulin doses.

“We had lost everything. We didn’t have an electric generator where we could keep (the insulin) cold,” Rosado said. “We had to, every day, wake up in the middle of the night and try to look for a place where we could find ice.”

Several months after Maria, Rosado’s family received a generator through Unidos por Puerto Rico, a nonprofit organization started by former First Lady Beatriz Rosselló.

It took the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority, known by the acronym PREPA, 11 months to restore power across the island, which is a U.S. territory. At its peak, all 3.4 million people on the island were without power. The next-longest outage was caused by the fast-moving Hurricane Ike in 2008, which knocked out power for 2.6 million people in Texas and Louisiana for up to three weeks.

“The main problem after Hurricane Maria was ... we had no communication whatsoever,” said Daniel Hernández, PREPA’s director of generation. That lack of communication made it more difficult for field crews to gauge the damage and respond to it, he said.

Hernández confirmed about 80% of the island’s grid network “was on the ground” after the storm.

The Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority, known by the acronym PREPA, took 11 months to restore power across the island – making it the longest blackout in U.S. history. At its peak, all 3.4 million Americans on the island were in the dark. (Ellen O'Brien/News21)

As many residents waited in the dark, PREPA auxiliary operator Jorge Bracero began filling the communication void. Bracero started sharing information on his Facebook page, including estimated power-restoration time frames for specific neighborhoods, as well as basic facts about how the electric grid works.

According to Bracero, these posts “completely blew up,” pushing him to create a professional page, which now has more than 121,000 followers.

He and his pregnant wife moved eight times over the next six months, staying with friends and family members who had power.

“Everybody in Puerto Rico that was here during the storms can say that they have a before and an after feeling of how to approach life,” Bracero said. “What we experienced was extremely horrible. And it made us into something new.”

If it’s not wind, it’s ice

In December 2013, a severe ice storm struck Lansing, Michigan’s capital and knocked out power for more than 50,000 residents for more than a week.

Older adults, people with disabilities, medicine-dependent residents and low-income families were most at risk during the outage, according to the Lansing Board of Water & Light’s Community Review Team.

During the Christmastime blackout, many weren’t just uncomfortable – they were angry.

“They just don't care,” Alice Dreger recalls thinking of the board, the city-owned utility company. After four days of huddling with her family next to the fireplace, a fed-up Dreger organized a protest with her husband.

Alice and Kepler Dreger spent nine freezing days without power after an ice storm struck Lansing, Michigan, in December 2013. Analysis by News21 shows that from 2008 to 2017, Michigan had 20 weather-related outages that lasted three days or longer – more than any other state. (Briana Castañón/News21)

“The irony was, after nine days without power, when a crew finally got here, it took 45 minutes to fix,” she recalled.

The ice storm led to investigations into the Board of Water & Light’s mismanagement of the storm and its emergency communications.

If there’s anger in Michigan, it’s because the extended blackouts keep happening.

News21 analyzed reports of electric disturbances collected by the Department of Energy from 2008 to 2017. In that time, Michigan has had 20 weather-related outages that lasted three days or longer – more than any other state.

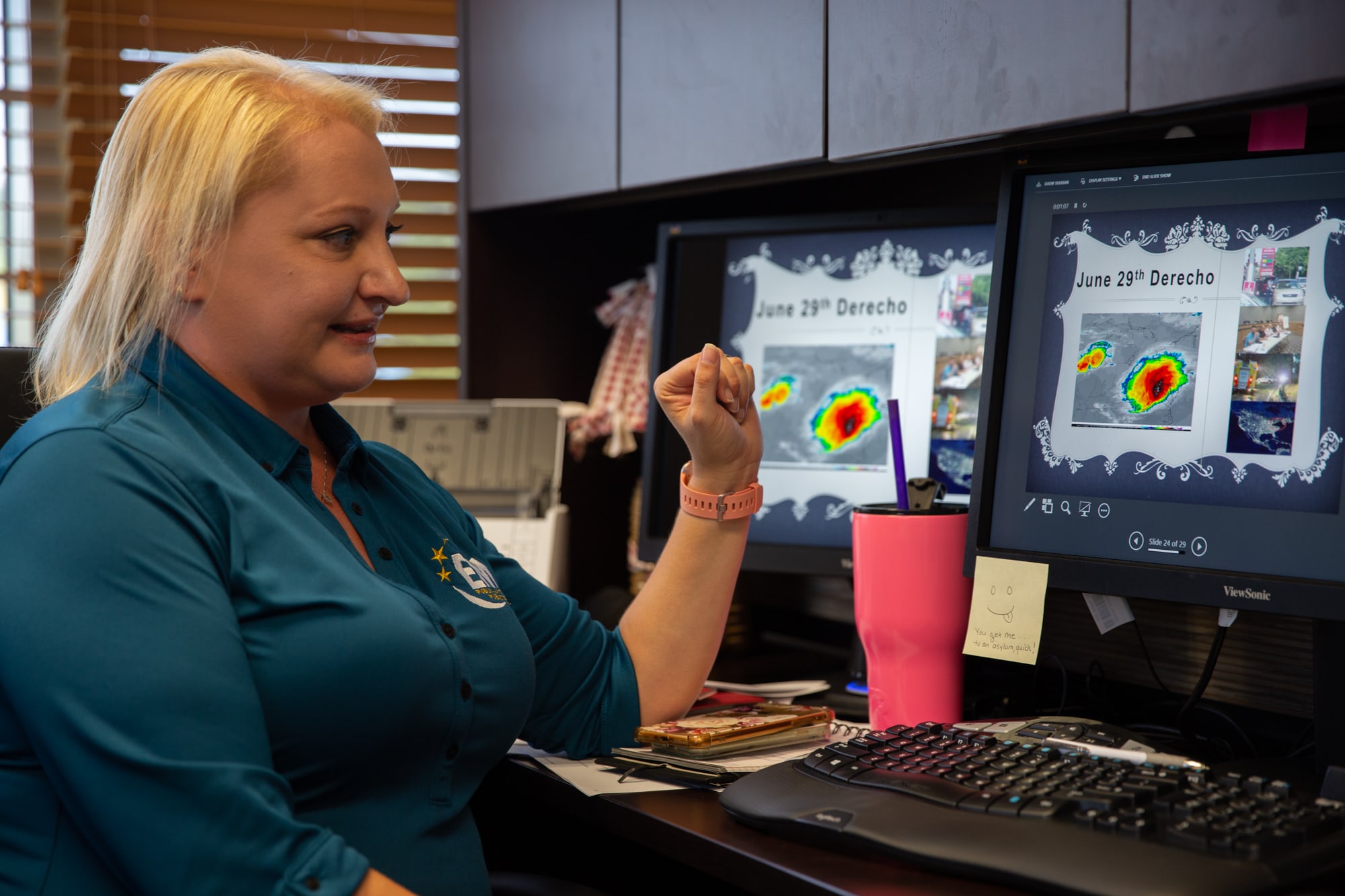

In July, the Michigan Public Service Commission published a statewide energy assessment that, among many recommendations, requested utilities review customer communication plans.

Better customer communication may not restore power, but it can restore calm, according to Pat Poli, director of the commission’s Energy Operations Division, who said anger always follows ambiguity.

“Information sharing is pretty critical to customer understanding and acceptance,” Poli said.

In 2018, the public service commission founded the Low Income Workgroup to identify energy issues important to low-income residents, such as health and safety, weather-proofing and energy efficiency.

Brad Banks, an energy efficiency analyst with the commission who’s the point person for the Low Income Workgroup, hopes it will keep an avalanche of problems from falling on these families. Without power for air circulation, mold can grow, which can impact low-income families for a long time, he said.

“If you have a house that has mold ... you’re living in a house that’s making you sick,” Banks said. “The incidents of childhood asthma in these houses is extremely high, which means your kid can’t go to school, which means you can’t go to work.”

According to a 2017 study co-authored by Seth Guikema, the president-elect of the Society for Risk Analysis and a professor at the University of Michigan, vulnerable communities put pressure on utility companies to more quickly fix the power grid.

“If you have a large chunk of people that can afford generators and buy them, then there’s less pressure on regulators to improve the system,” Guikema said.