‘Everybody is a first responder’ in disasters, police and firefighters say

CARSON, Calif. – With natural disasters increasing in frequency and intensity, first responders are finding it more difficult to reach and rescue the thousands of victims of floods, hurricanes, tornadoes and wildfires.

Throughout the country, many emergency units have fewer people to navigate disaster response, meaning they have to do more with less.

“So even if you were the slickest agency in the world, and you dealt with disasters all the time … if you train every day, a disaster is still called a disaster for a reason,” said Amy Donahue, a professor in the department of public policy at the University of Connecticut.

“Even if you devoted all of your resources to these rare events, you still would find yourself struggling to manage them.”

In 2015, the Federal Emergency Management Agency published “Operational Lessons Learned in Disaster Response,” which highlighted lessons learned over the past decade for first responders tackling disaster-related events. It also made recommendations, including more cooperation between agencies and communities, disaster-specific training and more efforts to help individuals fend for themselves.

The report based many of its suggestions on a 2006 study published a year after Hurricane Katrina – which Donahue co-authored – that emphasized poor communications, uncoordinated leadership, weak planning, resource constraints and limited training and exercises as areas in need of improvement.

“Even if the last generation learned those lessons,” Donahue said, “the next generation better learn them because the disaster is going to do exactly the same thing again.”

In southern Louisiana, St. Bernard Parish District Fire Chief Mike LeBeau said he went through Hurricane Katrina with 420 people in two shelters and limited resources. They made do with what they had until a relief force came in – from Canada.

“Because we felt like everything was going to the city (New Orleans) instead of coming to us, there was some bad feelings there,” LeBeau recalled. “Not toward the city themselves, but against the federal programs that are in place to offer aid. I kind of thought (the federal government) was very slow to react.”

Mike LeBeau, chief of the St. Bernard Parish District Fire Department in Louisiana, is a paramedic as well as a firefighter, so he routinely is assigned to run storm shelters. “I didn't really like it. Every fireman wants to be on that fire truck,” he said. “But after Hurricane Katrina, after having the devastation that we had and caring for the people that I cared for at the shelter, I have a different mindset on that now.” (Ellen O'Brien/News21)

Those lessons changed his mind about his department’s ability to respond.

During Katrina, the Fire Department had to commandeer private boats to rescue people from floodwaters because it didn’t have its own. Now, it has a swift-water rescue team.

“We do a lot more training now,” LeBeau said. “We're constantly training on different tactics and procedures.”

Experts say it’s almost impossible to be fully prepared.

“The next disaster is never going to be the same,” said Louise Comfort, former director of the Center for Disaster Management at the University of Pittsburgh. “It's important to go through those events and learn them, but the hard part is anticipating what the next disaster is going to be. While I think it's very useful to do after-action plans and identify what the failures were in that particular instance, those lessons need to be projected forward.”

The number of career firefighters has increased over the past three years, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, but smaller communities still rely on volunteers as their primary first responders. And the number of volunteers is decreasing.

“In most of the country, volunteers are the predominant workforce protecting the country,” Donahue said. “And so even during disasters, a lot of the help and work is done by volunteers.”

Of the nearly 30,000 fire departments in the U.S., about two-thirds are all-volunteer. Since 2015, the number of volunteer firefighters has fallen to 682,600 from 814,850, according to the National Volunteer Fire Council.

“The bottom line is that people have a lot less time than they used to,” said Natalie Simpson, associate professor of operations management and strategy at University at Buffalo.

The number of emergency calls to fire departments continues to increase nationally, according to a National Fire Protection Association Survey, and the range of services firefighters are expected to provide is expanding.

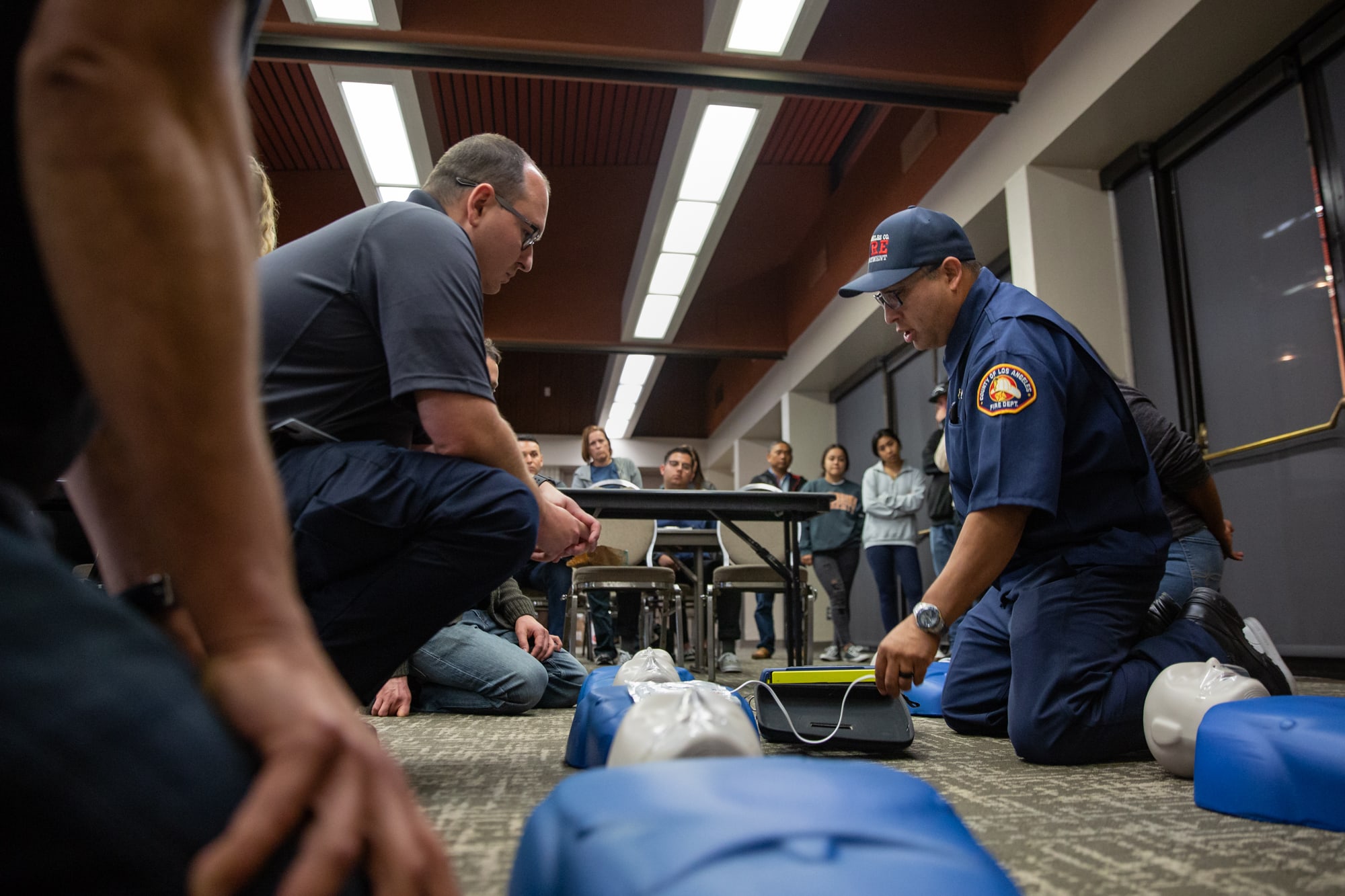

Both career and volunteer firefighters are now trained in emergency medical services and multihazard responses. It’s rare that they respond to actual fires, and even rarer to a natural disaster. Still, experts say they need to be prepared.

“For safety's sake,” Simpson said, “there is a lot more training now than there ever was, so this will continue to be a problem.”

Filling the gaps

Mutual aid agreements, which establish the terms of sharing resources in a pinch, help jurisdictions coordinate disaster preparedness.

Although some agencies use formal agreements to share resources, many communities are used to assisting neighboring departments, especially in disasters.

Raymond Oliver was in his Hamilton, Mississippi, home the night of April 13 when a pair of tornadoes hit the state. As the storm grew stronger, Oliver said he heard a roar from the wind like he had never heard in the 66 years he lived there.

Oliver is the fire chief of Hamilton’s fire department, staffed entirely by a dozen volunteers. At first, he and his wife hunkered down in the hallway of their home, but when his fire station radio began to chirp with calls, he knew he had to act.

Navigating his pickup around downed trees and debris blocking the dark road, he found his way to the station – now a pile of rubble covering its five fire vehicles.

Using his own truck, Oliver responded to the disaster calls and eventually was joined by his volunteer crew.

Hamilton’s station served about 1,400 people in a town with one traffic light and one main highway; the next closest station is 14 miles away. The other 12 all-volunteer stations in Monroe County came to Hamilton’s aid, Oliver said.

“My firemen, along with numerous firemen, were out that night – and it was still thundering, lightning and raining and gutting trees – going house-to-house searching for people,” he said.

The towns have a mutual aid agreement to pool resources, which allowed them to effectively respond to a devastating event that exceeded its station’s capabilities.

“I didn't have to call them,” Oliver said. “They automatically come if they know we’re in this situation.”

The Monroe County fire departments, along with those from nearby counties and such states as Alabama, stepped in to help Hamilton rebuild and recover.

“We do not have a written mutual aid agreement with Alabama,” Oliver said, “but in a situation like that, we don't care. We go help.”

But in large-scale disasters, local help likely isn’t enough.