People with disabilities and older adults left out in the storm

ST. THOMAS, U.S. Virgin Islands – Elegant cruise ships dock in the ports of St. Thomas daily, bringing tourists to parts of the islands that appear to be fully recovered from the 2017 Hurricanes Irma and Maria.

But a few miles west, in a neighborhood speckled with roofs capped by blue tarps, just past an old motorcycle and down more than 100 crude steps, lives a former U.S. Olympian still waiting for repairs to his damaged house.

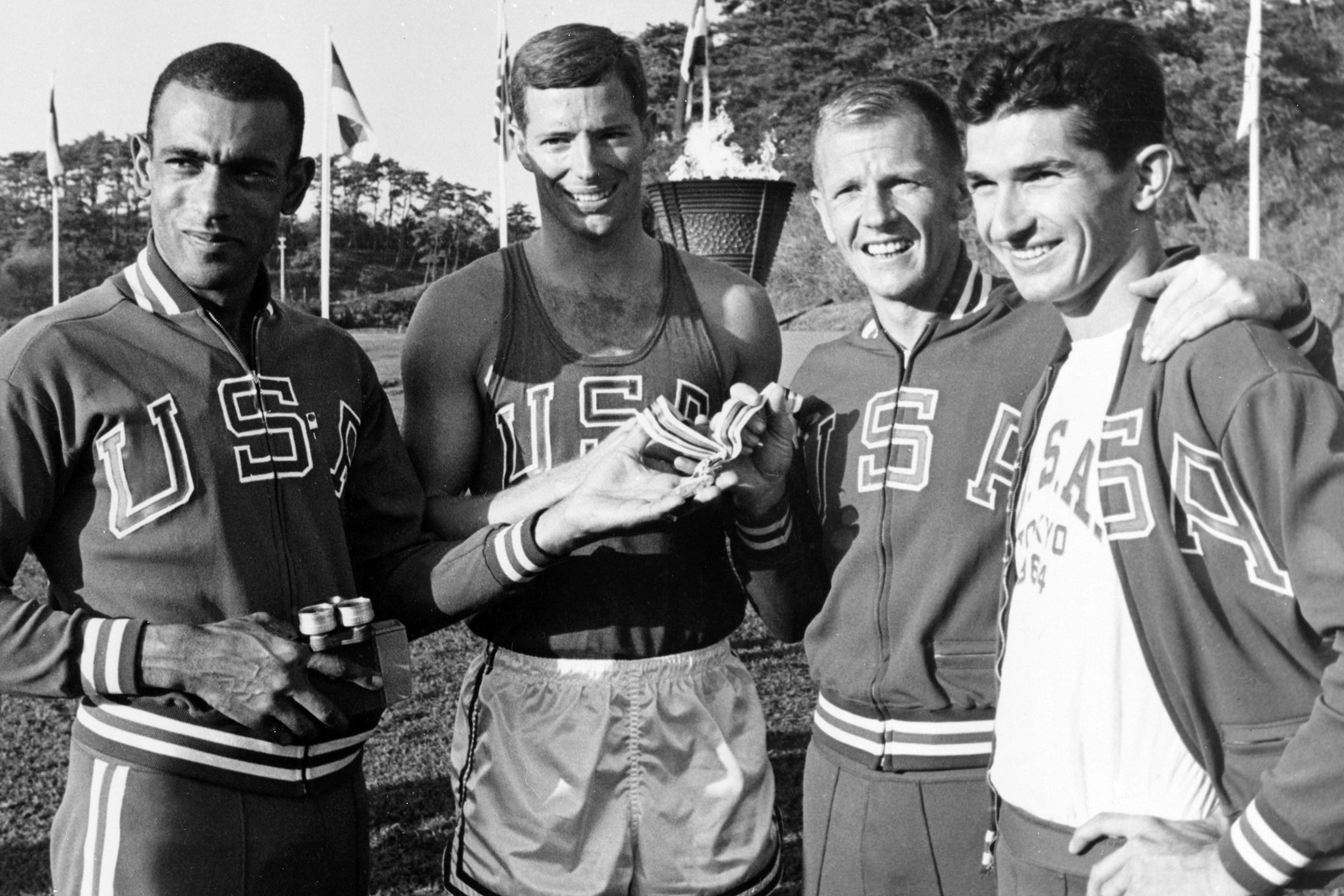

Like many older people and those with disabilities on St. Thomas Island, Jim Kerr, 78, lives alone. Although he no longer can see the silver medal he received as part of the 1964 Olympic pentathlon team, the pride of the win is fresh in his mind.

During Hurricanes Irma, Maria and Harvey in 2017, older adults and those with disabilities did not fare well, according to a May 2019 General Accountability Office (GAO) report that criticized the Federal Emergency Management Agency response. The report called for more support, although it recently has been cut, advocates contend.

Kerr, who has been blind for several years, is gradually losing his hearing, too. Although he is fiercely independent, the hurricanes made staying in his rural home difficult. After Irma, he spent hours trying to climb up the mountainside to get help. In the process, he lost his cellphone and realized there are things he can no longer do on his own.

For Kerr and others with disabilities living in the U.S. and its territories, the days, months and years of natural disaster recovery often are fraught with delays, discomfort and danger, according to advocates for the disabled and elderly, and the survivors themselves. Because resources to assist older adults and people with disabilities have decreased recently, advocates are concerned about the next storms, wildfires and floods.

“I dread – literally dread – having to go through that again ever,” said Felicia Brownlow, director of the Center for Independent Living in the U.S. Virgin Islands, who was critical of assistance provided to frail elders and people with disabilities after back-to-back Category 5 hurricanes hit the U.S. territory in 2017.

When a storm hits, understanding who is supposed to care for people is often unclear, and that puts lives in jeopardy, officials and advocates say.

The GAO report examined FEMA’s response in the Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, Florida and Texas. In the aftermath of those enormous storms, older adults and those with disabilities had trouble traveling to shelters and obtaining medicine, food, water and oxygen. Some shelters lacked appropriate showers, toilets and other accommodations for those with special needs.

“Nonprofit officials in Florida and Puerto Rico described incidents of shelter residents holding up sheets around other residents whose impairments prevented them from accessing the restrooms so that they could relieve themselves in common spaces of the shelter,” according to the report.

Hurricane survivors reported being confused by questions on FEMA’s application form for assistance, which may have led to fewer people reporting their disabilities – making it more difficult to help people in need.

Advocates said that was the case in the Virgin Islands, which has one of the largest populations of people with disabilities in the U.S. An estimated 15.3% have a disability, but only 3.5% who registered with FEMA after Irma and Maria answered “yes” to having a disability, according to the GAO report, which calls for improved application forms.

Kerr, a two-time Olympian, said he was disappointed by the obstacles in registering with FEMA for housing assistance. He said he had a hard time hearing the employee who helped him fill out forms.

“I couldn’t make use of the one thing that would have been easy,” said Kerr, who, nearly two years after the hurricanes, is still looking for a way to rebuild his house.

In his younger days, he said, he would have picked up a hammer and done the work himself.

“You have to accept that you can’t go down that road that’s not open to you any longer,” Kerr said. “That’s why the FEMA thing, fixing your house, was so important.”

The three major Gulf Coast hurricanes in 2005 exposed special risks faced by vulnerable people. An estimated 1,330 people were killed in Louisiana and Mississippi during and after Katrina. At least 71% of deaths in Louisiana people were older than 60, and 47% were older than 75, according to a report by the advocacy group, AARP.

In response, AARP convened government officials, emergency preparedness and response experts, and advocates for the elderly and disabled in Texas. That meeting generated a 2006 report, “We Can Do Better,” which called for better evacuation plans and protections.

But 13 years later, more needs to be done, advocates and officials say.

“When I started coming into emergency management, I kept saying, ‘Why are we repeating history?’” said Sadie Martinez, who works for the Colorado Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management.

The 2019 GAO report made seven recommendations to FEMA. Some have to do with clearer lines of responsibility, better intake forms and more communication in disasters. FEMA mostly agreed to six of the changes but said one, to improve communication about “disability-related information” to all FEMA programs, was unreasonable because of funding.

Marcie Roth, former director of FEMA’s Office of Disability and Integration Coordination, started a program in 2010 to train and deploy experts – disability integration advisers – to hurricanes, wildfires and floods to help older people and people with disabilities.

They were extensively trained to recognize when sign-language interpreters and hearing aids, for example, were needed and helped survivors with functional needs find appropriate places to live, Roth said.

In 2018, the year after Hurricanes Irma and Maria, FEMA reduced the number of disability integration advisers sent to the field to five, down from an average of 55. Instead, it now trains all FEMA employees who are deployed to disaster zones. But the training is only 30 minutes, Roth said, and not as extensive as what was conducted in the past.

Linda Mastandrea, the director of FEMA’s Office of Disability Integration and Coordination, said in an email that her office is providing “all FEMA employees a baseline understanding on disability issues.”

A slow recovery

Some residents of the U.S. Virgin Islands said they feel forgotten, even now, almost two years after Hurricanes Irma and Maria.

“Every time you listen to the news, you hear, Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico, and it's like the Virgin Islands doesn’t exist,” said Ruby Simmonds Esannason.

According to a report by the U.S. Virgin Islands Housing Finance Authority, the territory’s entire population of 100,000 was affected. More than 14,000 homes were damaged, and more than 85% of structures required repairs.

Still, the official death toll is five – a number that Simmonds Esannason calls “grossly, grossly inadequate.”

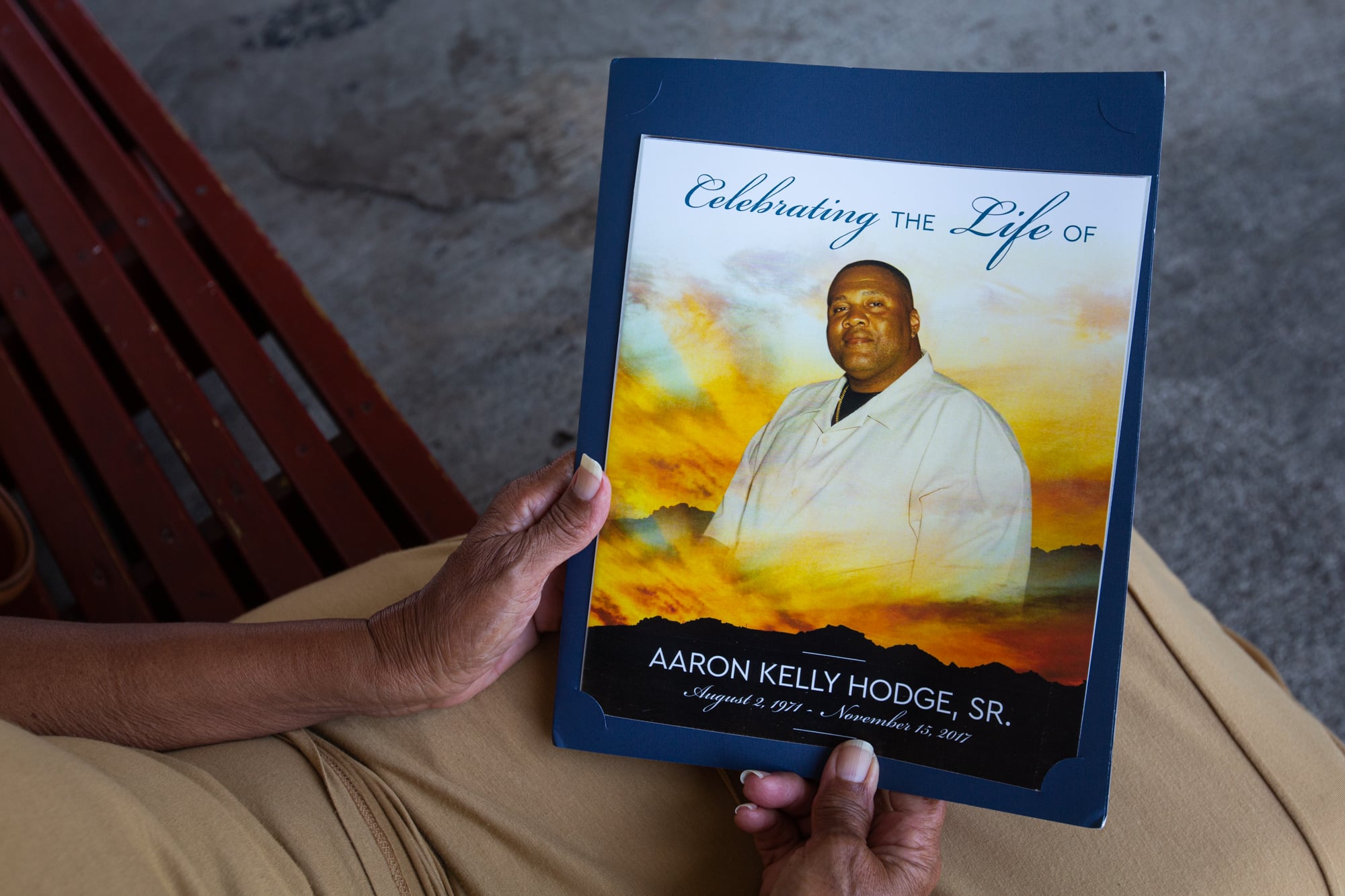

The death toll does not include at least 49 people who died after medical evacuations, she said. Her son-in-law, Aaron Hodge, was evacuated with other hospital patients from St. Thomas to St. Croix, then Puerto Rico and finally Atlanta – where Hodge died.

Almost 800 people, including hospital patients and people on dialysis, were medically evacuated from the Virgin Islands, according to a 2018 press release from the territorial legislature. Simmonds Esannason said no one told her family Hodge was being evacuated.

Because Hodge’s death was not attributed to the hurricanes, Simmonds Esannason said her daughter had to pay to have his body flown back to St. Thomas.

Simmonds Esannason later testified before Congress, asking for changes to the medical evacuation process and a revision to the storm’s death toll.

“It's hard to think of someone dying, alone and away from their families, and that's what happened in our situation and happened to many other people,” she said.

Ruby Simmonds Esannason has been pushing for safer medical evacuations since the death of her son-in-law, Aaron Kelly Hodge, Sr. He was medically evacuated from the U.S. Virgin Islands during the 2017 hurricane season and died in Atlanta. (Anya Magnuson/News21)

On the island of St. Croix, many of the 50,000 residents describe being trapped in their homes during the hurricanes with no electricity and no idea when help would come.

“You don’t even know where to go, what to do,” said Carmen Huertas, who is blind. “You feel completely lost.”

Huertas, who’s in her 50s, lives with her parents on the western side of 84-square-mile St. Croix. The framework of their home of 27 years is all that remains. Huertas and her parents live in a one-bedroom concrete storm shelter on the property while they rebuild their home with $27,000 in FEMA funds.

It’s not nearly enough, the family says.

Norma Huertas, Carmen’s mother, estimates the full cost of rebuilding will be $120,000. The family applied for another FEMA program in May, and if they don’t receive aid, the family may have to leave the island for Puerto Rico.

The choice is difficult because Guillermo Huertas, Carmen’s father and Norma’s husband, has vascular dementia, a degenerative disease.

“I don't want him to get lost in another place,” Norma said. “In this neighborhood, everybody knows him, so if he gets lost, they can bring him back.”

Standing in the ruins of her bedroom for the first time since the hurricane, Carmen described her feelings as “Emptiness … a part of you is missing.”

The family was trapped in their home for two days after the storm. A neighbor found them after noticing a fallen tree blocking their door.

Carmen Huertas, 54, who is blind, remembers the layout of what used to be her home on St. Croix. Standing in the ruins of her bedroom for the first time since 2017, Carmen described her feelings: “Emptiness … a part of you is missing.” (Anya Magnuson/News21)

The Huertas family home on St. Croix was destroyed by Hurricane Maria in 2017, and only the back portion has been reconstructed. The rest remains open to the elements. (Anya Magnuson/News21)

Registries help track the vulnerable

After the hurricanes, lawmakers in the Virgin Islands established a registry to help first responders track and older people and those with disabilities.

Territorial Sen. Dwayne DeGraff said the registry will help people receive help more quickly after a disaster, so they wouldn’t have to “stick it out for days.” Many states, territories, and counties have registries, but their purposes vary.

Florida’s registry operates as a signup sheet for special-needs shelters, which provide more accessible cots and medically trained staff, among other services.

During Hurricane Irma, many people in Florida didn’t know they needed to sign up for these special-needs shelters in advance, said Jeff Johnson, state director of Florida AARP. That resulted in overwhelmed facilities.

In New Jersey, first responders use a registry to locate the elderly and people with disabilities.

“It doesn't necessarily mean that they're going to be rescued first, but it just gives an awareness of what to expect,” said Luke Koppisch, deputy director for Alliance Center for Independence in New Jersey.

Colorado doesn’t have a registry, and state representatives don’t want one.

“It puts the false hope of security in people with disabilities that somebody is coming to rescue you,” said Sadie Martinez, an access and functional-needs coordinator in Colorado’s Division of Homeland Security Emergency Management.

She wants Coloradans to develop their own emergency plans and not rely on a rescue team that may never come.

But self-help isn’t easy, say Virgin Islanders who survived the storms.

Gerard Evelyn, 49, who is diabetic and visually impaired, survived Maria in his St. Croix home with nothing but his radio and the sound of the wind and devastation. It was the first hurricane he experienced after losing his vision six years earlier.

“Before, I could see the devastation. ... Now I'm listening to it,” Evelyn recalled. “It sounds almost like … one of those big Boeing jets when it's about to land, but amplify it like 100 times.”

In the days after the storm, the most important sound came from the radio, he said: “That was our only form of communication, really, with the government.”

Evelyn’s roof, still covered with a blue tarp, leaks, causing floor tiles to crack. He uses duct tape to keep the tiles in place.

He relied on the goodwill of his neighbors who have generators to keep his insulin cold and to charge his cellphone. He received a gasoline generator of his own from the American Red Cross months later. The generator required flipping a switch and pulling a string to start, which Evelyn said might be too difficult for some people with visual impairments. Maybe solar would be better next time, he suggested.

No easy answers

Because every person is different, Evelyn said, “you have to assess the individual needs.”

Advocates agree but say solutions aren’t easy.

Marcie Roth, now CEO of Partnership for Inclusive Disaster Strategies, worked this year with members of Congress to introduce legislation establishing a National Commission on Disability, Aging Rights and Disaster, and to develop research centers to study how to better serve vulnerable populations in disasters. It’s needed, Roth said, because there are disagreements within the disability and aging communities about what needs to be done to help people plan for disasters and survive them.

Back at his modest house overlooking the ocean, Jim Kerr, the former Olympian medalist, chopped raisins with tedious precision. When he finished, he slowly ran his hand over the counter top to be sure he’d gathered every piece. It’s a short journey from the kitchen to the deck, where chirping birds awaited him.

“It is so pleasant a place,” he said with a smile. “Next time you think about wondering why I would be in this place, it's that peaceful aspect of it all and the blend of it all.”

News21 reporter Anya Magnuson contributed to this report.

Carly Henry, Anya Magnuson and Ariel Salk are Hearst Foundation Fellows.

Republish this story

Our content is Creative Commons licensed. If you want to republish this story, you may download a zip file of the text and images.