Wildfire-vulnerable communities search for ways to live with growing threat

SHINGLETOWN, Calif. – Unless it’s Sunday, Kelly Loew is steering her rusty-red Jeep down the same mail route in Shingletown, as she has six days a week for the last seven years. But she delivers less mail these days as California’s persistent wildfires drive residents away.

Last year, California experienced its deadliest and most destructive wildfire season. Shingletown, nicknamed Little Paradise, is one of the state’s most wildfire-vulnerable communities.

Despite the National Interagency Fire Center recording federal fire suppression costs quadrupling since 1989, the damage caused by wildfires has increased fivefold.

“The fear is palpable,” Loew said. “When I drive home through my neighborhood, I see tinderboxes everywhere.”

According to data from the National Catastrophe Service, wildfires over the past decade have resulted in more than $52 billion in insured losses across the country. Flames have burned nearly 49,000 structures across the U.S. since 2014, according to the National Interagency Fire Center. That’s more structures lost than in the previous 14 years combined.

“We shouldn't be surprised that we're seeing not only our cities growing but lots of people taking over what had been rural landscapes and making them an urban environment,” said Stephen Pyne, a wildfire historian. "People like to live in lots of areas that are full of natural hazards and it's very hard in the American system to tell people they can't do what they want on their property."

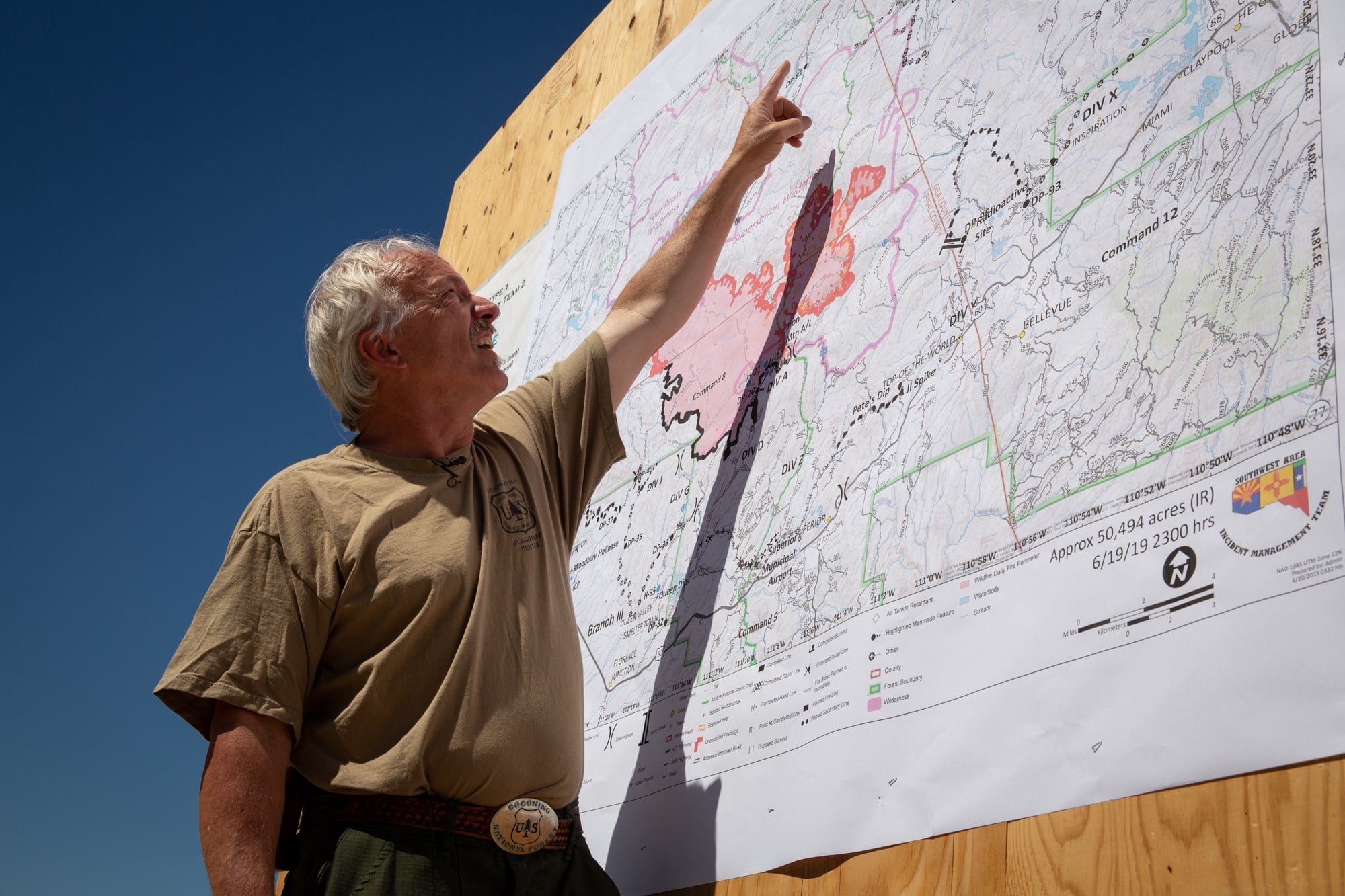

This summer, the Woodbury Fire northwest of Superior, Arizona, burned close to 124,000 acres and prompted a mandatory evacuation of Roosevelt and nearby communities. It’s the fifth largest wildfire in state history.

“My mind was on overload. I have to pack this, I have to pack that … Plus you have to pack your personal stuff,” said Pat Spencer, a business owner in Roosevelt, Arizona. “Everybody was like, ‘Why are you packing it up? I said, ‘Just to be safe, rather than sorry.’”

Among her most important possessions: three figurines of angels embracing firefighters. Spencer has six firefighters in her family. Three of them – her son, husband and nephew – spent more than a week battling the Woodbury Fire, which broke out June 8.

Last year, according to the National Interagency Fire Center, Arizona had 838 wildfires more than the U.S. state average – placing it among the top 10 in the nation. The data show that in the first six months of 2019, wildfires in Arizona have burned more land than was burned in all of 2018. Seven other states, including Alaska and Rhode Island, have shown the same trend.

Over the past three decades, the number of wildfires declared major disasters by the Federal Emergency Management Agency has been steadily growing, with 19 since 2009. Nearly 68% occurred in California, Colorado and Oklahoma; the others were in Texas, Washington, Tennessee and Montana.

The cost of wildfire recovery often falls to individual states. To get federal dollars flowing, the governor has to request a disaster declaration and FEMA must recommend it to the president, who can deny or approve it.

But while the number of wildfire disaster declarations has grown in the past two decades, only 16.2% of wildfires larger than 100,000 acres have been declared major disasters, which is about 0.002% of all wildfires in the past 20 years.

When Pat and John Spencer returned to their home in Roosevelt, Arizona, after a five-day evacuation, three firefighter figurines were among the first things Pat unpacked. She has six firefighters in her family; three of them – her son, husband and nephew – spent more than a week battling the Woodbury Fire in June. (Anton L. Delgado/News21)

Tinderboxes everywhere

“Being human means there’s risk of some sort in your life,” Loew said. “If you’re looking for a quiet mountain town with a good community, a good school and great people, this is the place to be … I don’t know why people wouldn’t want to live here.”

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s 2010 Wildland Urban Interface report, Shingletown is an intermixed community, meaning “housing and wildland vegetation intermingle,” which increases wildfire risk.

The report shows over 39 million people across the country live in forested communities like Shingletown. More than half live in 10 states: Texas, North Carolina, Georgia, Pennsylvania, New York, California, Florida, Virginia, South Carolina and Alabama.

In California, more than 1.74 million residents live in such communities. Since the report came out in 2010, more structures have been burned in the Golden State than anywhere else in the United States.

The more than 41,000 burned structures in California is nearly 13 times more than the next state, Texas, which had 3,222 structures burned in the same time span.

“Fueled by drought, an unprecedented buildup of dry vegetation and extreme winds, the size and intensity of these wildfires caused the loss of more than 100 lives, destroyed thousands of homes and exposed millions of urban and rural Californians to unhealthy air,” according to a February report by the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, known as Cal Fire.

More than 25 million acres of California wildlands are classified as under very high or extreme fire threat. The report blames “climate change, an epidemic of dead and dying trees, and the proliferation of new homes in the wildland urban interface.”

Research by the University of Idaho in 2016, found that wildfires in the West have been made worse by higher temperatures associated with climate change. Warmer air has made forests drier, making vegetation more flammable and better wildfire fuel.

Shingletown, named after its historic production of wooden shingles, is considered vulnerable because of its average age of 61, its median household income of $42,000 – more than $18,000 less than the national median – and its location in the foothills of the Cascade Range.

To prevent larger wildfires, Cal Fire plans to grind down vegetation. Its top priority project is to create defensible space, along Shingletown’s main road, State Route 44.

In a low-income community like Shingletown, not everyone can afford to create defensible space. Some simply burn the flammable brush, known as slash, in their yards.

“Every slash pile being burned has the potential of getting away,” said Tom Twist, deputy chief of the Shingletown Fire Safe Council, which offers a program that gives residents access to a site to get dump flammable vegetation. “We want to reduce the chances of what we call doorstep burn piles.”

California Assemblyman Jim Wood said he's been working to find funding for wildfire prevention since wildfires in 2017 killed 44 people in Northern California, which until last year, were the most destructive in state history.

But in November 2018, the Camp Fire in Butte County killed 86 people and destroyed close to 12,000 structures. That made it the deadliest wildfire since the 1918 Cloquet Fire, which killed more than 450 people in Minnesota.

Wood, a dentist by trade, volunteered with local authorities to use dental records to identify victims in Paradise. Less than a month later, he proposed Bill AB-38, which would establish a $1 billion fund meant to financially aid low-income residents fireproof their homes. The bill passed but was stripped of funding.

“The legislative process is not perfect,” Wood said. “But the commitment I have to trying to find a funding source ... to help people protect their homes isn’t going away.”

California’s building code requires homes in fire-prone regions built after 2008 to have fire resistant roofs and siding, and other safeguards. This year, a similar amendment was passed in Oregon, which had the sixth most wildfires in 2018. Both codes require homeowners to pay for it.

In 2010, 40 million people in the country lived in forested communities, approximately 1-in-10 Americans. But despite the risk of wildfires, building projects continue to be approved in areas still recovering from previous blazes.